* This article has been published by Istanbul Policy Center (with Bianca Benvenuti)

Executive Summary

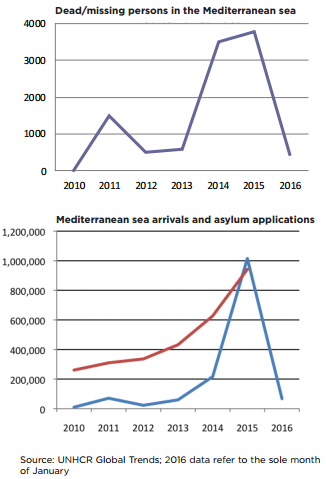

The European project has hit strong headwinds in tackling its most recent challenge. The refugee crisis has made institutional shortcomings and divisions between member states more visible than ever. The skyrocketing number of migrant deaths on European borders showed the world the European Union’s failure to find a shared solution to the crisis. Although blamed for reacting too late, European leaders have been working on a solution to the refugee crisis, and the efforts have become more visible since the European Commission published its “European Agenda on Migration” in May 2015. German Chancellor Angela Merkel, on the one hand, has been playing a central role in convincing her European counterparts to formulate a common response. On the other hand, a mainly Eastern European group led by Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán has been actively opposing nearly every facet of Merkel’s plan. In an effort to break the political and institutional stalemate, Turkey was brought into the game and became a key partner in “solving” the problem. Although the EU signed and sealed the deal with Turkey, confrontation between the two opposing factions in Europe persists. The issue has become not only a humanitarian crisis but also another important test for European integration itself after the economic crisis. This paper unfolds the story of the European response to the refugee crisis and the central role Angela Markel has played in initiating this. The German Chancellor has always been a leading figure in the EU; however, her position has become even stronger against the backdrop of the refugee issue. This position, of course, has come with a price.

Introduction

According to the United Nations High Commissioner on Human Rights (UNHCR), the total number of forcibly displaced people worldwide has steadily increased over the past four years, far surpassing 60 million in 2015. The term global migration crisis or global refugee crisis has been used to describe the coerced movement of millions escaping their home countries that are plagued by warfare, instability, disasters or poverty. The beginning of this crisis is linked to the onset of the Arab Spring in 2011. Some scholars classify it as a political crisis, rather than a refugee crisis, because leaders have failed to respond to this issue. The European migrant crisis, in particular, describes the specific situation faced by European Union member states and institutions in receiving this massive influx of migrants and refugees. A political impasse, which will be analyzed in detail in this paper, resulted from European member states’ ineptitude in dealing with the migrant flux. In fact, the number of migrants reaching European coasts began to surge in the same year as the onset of the Arab Spring; yet by 2014 the migration issue was still not a priority on the EU agenda. Ironically, in 2014, Italy and Greece, the countries that were, and still are, the most affected by the migration flux, held the Presidency of the Council of the European Union. Meanwhile, Jean-Claude Juncker was inaugurated as the first “elected” president of the European Commission, and Donald Tusk began activities as the new President of the European Council. With time passing and the number of migrants arriving to European territory rapidly surging, the EU heightened its sense of emergency, and the migration issue finally became the EU’s top priority. Yet, the institutional response was still much later.

In summer 2015 German Chancellor Angela Merkel emerged as a leading figure in the Europe-wide response to the refugee crisis. On August 31, she issued a call to arms, declaring, “if Europe fails on the question of refugees, it won’t be the Europe we wished for.” Some observers commented on Angela Merkel’s reaction, defining her as “Europe’s conscience” for her emphasis on European values and her interest in a collective response to the migration crisis. Others pointed at her audacious pragmatism, underlining that her leading role in the EU response is purely realpolitik. According to government data, nearly 1.1 million people entered Germany in 2015 in search of asylum, about five times the number registered in 2014. It is reasonable that absorbing the highest number of migrants, Germany calls for a common European response. Thus, Merkel’s policies could just as well be a mixture of realpolitik and solidarity. Although Merkel’s impetus for the call to reformulate Europe’s refugee policy remains ambiguous, what is sure is that she has been the only European leader to stand up and suggest a common EU action to face the migration crisis.

The Quest for a Common Response to the Migration Crisis

In May 2015 the European Commission drafted the “EU Agenda on Migration,” elaborating on a comprehensive response to the migration emergency and setting political priorities. One of the most sensitive and controversial ideas of the Agenda has been the establishment of a temporary “Relocation System” to redistribute asylum seekers among member states, together with a “Resettlement System” to welcome an additional number of 20,000 migrants from outside the EU. The Dublin regulation, which established regulations for assessing protection claims in the first country where a migrant is registered, put the weight of the migration pressure upon recipient countries, namely Italy and Greece. Counter to this, the Commission proposed a model to allocate responsibility between member states on the basis of a new criteria that is including GDP, population, unemployment, and other similar indicators. In its proposal, the European Commission established a mandatory quota system to redistribute 40,000 migrants that are in Greece and Italy to other member states. The proposal, which Angela Merkel supported since its first draft, immediately sparked criticism among some countries. Polish Prime Minister Ewa Kopacz openly declared opposition to any kind of mandatory quota system and agreed to admit only Christian Syrian families into Poland. The Czech Prime Minister Bohuslav Sobotka issued the same critique, followed by the Slovak government’s declaration to join the blocking minority along with Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán. It soon became clear that the proposal stood no chance of being unanimously accepted.

The massive exodus from Syria during summer 2015 and the member states’ diverging reaction to it was a watershed in crisis management. In August, Merkel declared that Germany would open borders to Syrian refugees, triggering an even larger influx of people trying to reach the country as well as fueling growing frustration among the Balkan countries. In early September, thousands of refugees marched from Budapest, because they had not been allowed to leave Hungary by train. As Germany was welcoming migrants in Munich, Orbán was accusing Merkel of “moral imperialism” for her open-arm refugee policy. Two camps revealed opposing strategies for solving the migration crisis. The Visegrad group, under the leadership of Orbán, insisted that the EU’s efforts should be directed toward strengthening its external borders and stopping the flow of migrants coming from the Aegean by building walls and fences. Angela Merkel opposed the idea of fences that would keep civilians out and could potentially leave Greece alone to deal with the crisis, as well as strengthen the understanding of “fortress Europe.”

Tension among member states surged and turned into an open conflict during the Justice and Home Affairs Council on September 14. On this occasion, the relocation proposal was forced through and adopted by a qualified majority: the Council agreed to redistribute 160,000 Syrian refugees, a sharp rise from the 40,000 initially proposed, who are in Greece, Italy, and Hungary to other member states within a time span of two years. On paper, Angela Merkel’s proposal had won. However, the tense atmosphere revealed the deep split among countries, with the Eastern block fiercely opposing the plan, claiming that the relocation would draw more migrants to Europe and disrupt society. Slovakia went so far as to push ahead with legal action over refugee quotas by taking its complaint to the European Court of Justice. During fall 2015, the decision of several countries, including Austria, Sweden, France, and Germany, to close their borders and suspend Schengen regulations further complicated the situation. This opened a troubling debate over the future of the Schengen, as many started suggesting that the visa-free area was collapsing under the weight of the refugee crisis. In addition, member states did little to actually implement the plan, and the relocation/ resettlement program fell short of expectations: by the end of January 2016, less than 500 refugees were actually resettled from Greece and Italy as a series of logistical obstacles stood in the way of carrying it out. In its first report on the relocation and resettlement plan published in mid-March 2016, the Commission called on member states to increase their pledges and shorten the time needed to process applications. However, the second report, published in April, stated again that progress is unsatisfactory, especially concerning the relocation program.

Alternative Ways to Deal with the Crisis: Turkey and Beyond

Since no unanimous agreement was achieved over how to manage refugees in EU territory, efforts were pointed at addressing the issue with countries of origin and transit. As the Eastern and Balkan route became increasingly important during 2014- 2015, one actor was identified as the provider of the solution to the European chaos: Turkey. To avoid border closure, Angela Merkel regarded Turkey as a potential partner and took a leading role in Turkey’s negotiations with the EU. In the European Council meeting of October 15, EU leaders, together with Turkey, drafted the EU-Turkey joint action plan. It included significant political and financial incentives for Turkey in return for its cooperation in preventing illegal migration to the EU – i.e. an initial payment of 3 billion EUR from the EU to support improving Syrians’ conditions in Turkey together with a promise from Brussels to speed up the accession negotiations and visa-free travel for Turkish citizens. In addition to the EU-Turkey deal, during the Valletta Summit on migration in November 2015, EU leaders met their counterparts from African countries to step up cooperation with countries of origin. The EU agreed to set up a 1.8 billion EUR fund to assist these governments in managing migration and refugees. By the end of November, it seemed that energy to address the refugee crisis would be directed toward finding a solution with third countries in order to assist both origin and transit countries in keeping refugees from entering Europe.

On March 7-8, 2016, EU leaders met with Turkey once again. The summit was expected to follow up on the November 2015 agreement, and according to the declaration drafted by the EU ambassadors, EU leaders were expected to close the Balkan route. However, Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte, who holds the current rotating Presidency of the Council of the European Union, together with German and Turkish Prime Ministers, substituted the draft agreement with a new deal. According to the new text, under the so-called “one for one” principle, one Syrian refugee from Turkey would be resettled in Europe for every one refugee that is readmitted to Turkey. Europe would take up to 72,000 Syrian refugees, although Turkey would accept many more from the Greek islands. Europe would also commit to pay up to an additional 3 billion EUR to Turkey in order to manage the refugees in its territory, lifting the visa requirement for Turkish nationals by the end of June and opening five negotiation chapters in Turkey’s accession process. In spite of frustration from several European leaders, outraged by an attempt to substitute EU decision-making with a controversial deal brokered by Berlin, the new plan was finally adopted in the March 17-18 meeting.

Although Merkel declared that the plan was devised and proposed by Turkish Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu, in reality it was the plan of the so-called “coalition of the willing” that has been in the pipeline for months. The European Stability Initiative (ESI) devised and published “The Merkel Plan” on October 4, 2015. The key element of this plan is that Syrians would submit their protection claims to Turkey, to be later safely transferred to a predetermined EU country. This offer would be limited to Syrians who are already registered with the Turkish Directorate General for Migration Management (DGMM) to avoid creating incentives for more migrants to travel to Turkey. Turkey would commit to take back all new migrants who reach Greece from a given date; this should discourage migrants undertaking the risky journey in the Aegean Sea toward Greece. The ESI plan had gone relatively unnoticed in the lead up to the November meeting; however, on January 28 in an interview with De Volkskrant the Dutch Labour Party leader Diederik Samsom revealed the plan’s origins, stating that it received support by Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte and a number of EU member states, including Germany, Austria, and Sweden. During the official meetings with Turkey in October and November 2015, none of the countries referred to the ESI plan. Instead, on the sidelines of the EU-Turkey summit, a presummit meeting took place between Merkel and the leaders of Sweden, Finland, Austria, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, Belgium, and Greece to discuss the implementation of a resettlement scheme for refugees from Turkey to the EU. The “coalition of the willing,” as it was branded after the meeting, was discussing the ESI plan. In fact, following the EU-Turkey agreement, Orbán declared that Germany struck a secret pact with Turkey to take in as many as half a million people. As a first step after the alleged secret pact, Turkey was deemed by Greece as a Safe Third Country— i.e. a country that is safe for asylum seekers of nationalities other than that of the country itself— on February 5. On February 11, NATO announced the deployment of its fleet in the Aegean Sea in a bid to end the flow of refugees crossing the sea into Europe from Turkey. In March, the EU-Turkey draft plan was formally revised. Moreover, on April 4, Greece started sending migrants back to Turkey. EU leaders could finally breathe a sigh of relief and declare that, after such a long discussion, they finally agreed on how to address the migrations crisis. However, the situation is not as resolute as it might seem.

Even if the plan can be considered as an improvement toward a shared European response to the migrant crisis, the real issue is its implementation. The relocation of migrants from Turkey to Europe will follow the Voluntary Humanitarian Admission Scheme proposed by the European Commission in late 2015. This means that the final decision on whether or not to welcome any migrants rests with participating states. Given Eastern European opposition to the relocation plan from Greece and Italy, it is uncertain if these countries will agree to accept any refugees. In fact, as of mid-May 2016, Finland, Germany, the Netherlands, Sweden and Lithuania had resettled a total of 177 Syrians from Turkey.

Moreover, many human rights groups have voiced concern over the plan, saying it is in violation of international law. Human Rights Watch’s director Bill Frelick declared “the parties failed to say how individual needs for international protection would be fairly assessed during the rapid-fire mass expulsions they agreed would take place;” therefore, the deal “contradicts EU principles guaranteeing the right to seek asylum and against collective expulsions.” Similar critiques came from Amnesty International, which declared, “the very principle of international protection for those fleeing war and persecution is at stake.” UNHCR has expressed concerns over the collective expulsion of refugees legally prohibited under the European Convention of Human Rights.

For Angela Merkel, the final plan approved on March 18 was a triumph. She managed not only to step up to the plate amidst growing resistance but also to gather support for her plan despite this. However, her current situation is not ideal: once again, she is carrying the weight of a plan she envisioned, including its risks. The fact that Diederik Samsom presented the plan for the first time and that Ahmet Davutoğlu officially proposed it as his own shows the extent to which the German Chancellor is looking to share responsibility.

Angela Merkel on the move: Saving Europe, losing Germany?

Angela Merkel has been Chancellor of Germany since 2005 and the leader of the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) since 2000. In addition to her political career in Germany, she has been also acting as the “unelected” leader of the European Union. Merkel’s leadership in the European Union came to the fore first in the Eurozone crisis together with her Federal Minister of Finance, Wolfgang Schäuble. They have been important figures behind the rough austerity policies together with the Troika, formed by the European Commission, European Central Bank, and International Monetary Fund. She has also been the unofficial and contested leader in discussions on Europe’s refugee crisis. She has been fighting for possible ways to settle this crisis, first inside the EU and then with Turkey. The concepts of “shared humanity” and “moral responsibility” have marked her discourse throughout 2015. However, the timing of this leadership has not been the best for her political career either at home or abroad. The austerity measures that have been forced upon member states have already turned several EU members against her leadership, and at home she faced competition from the far right.

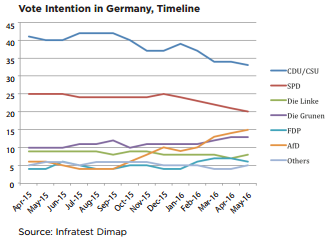

When we look at the migration issue in detail, the challenge has been to figure out how to slow down the refugee flow without sacrificing the humanitarian side. This has been a tricky test and a catalyst for extreme movements in Europe. For example, state elections in Germany (in BadenWürttemberg, Rhineland-Palatinate, and SaxonyAnhalt) have been an important sign of the forthcoming federal elections in 2017. The rightwing extremist party Alternative für Deutschland (AfD)—which was established in 2013 but could not make it into the German Bundestag because of the five percent threshold—has been on the rise. In Baden-Württemberg and Rhineland-Palatinate, the party won the third highest amount of votes, receiving 15.1 percent of the vote (23 seats) and 12.6 percent of the vote (14 seats), respectively. In Saxony-Anhalt, furthermore, the party came in second with 24.2 percent of the vote and 24 seats. This situation is alarming, not only for Germany but also as a symbol of the rise of European extremist movements elsewhere. The AfD has been called “the most successful protest party in Germany’s post-war history.”

In contrast to the AfD’s rise, Angela Merkel and her party are declining. Parallel to the beginning of the bargaining with Turkey and the visa dialogue in the European Union in October 2015, support for CDU/CSU began to decline. According to Infratest Dimap survey in May, CDU/CSU, which together forms the parliamentary bloc known as the Christian Democrats, would receive 33 percent of the vote if there were elections tomorrow. This is considerably lower when compared to 2013 elections, when the CDU/CSU vote stood at 41.5 percent. Although support for the CDU/CSU has its ups and downs, overall the trend has continued to move downward. Further, the division between CDU and CSU is more visible than ever and will require attention in the near future. No doubt the evolution of the political crisis in the field of migration will play an important role in the vote distribution. One fact is very clear: German society is divided, and the tone of this debate is more aggressive than ever.

Turning our focus to individual European societies, in particular German society, another question comes to mind: can Merkel’s push toward her refugee plan cause even more fraction within the EU? There is already an extensive debate surrounding this question. Seemingly, Merkel still believes in a European solution to this problem via the European Commission plan and agreement with Turkey. It is safe to say, however, that what has been done so far is too little, and there will be further flows in the near future, once again threatening to unravel the moral fibers of European societies.

Conclusion: Too little, too late

The European migration crisis has revealed the many weaknesses of EU institutions. The response was late in coming, and the subsequent discussion on the relocation and resettlement of refugees has nearly exhausted EU member states and institutions. After the rapid surge in the number of migrants reaching European shores, as well as a record number drowning in the Mediterranean Sea, Angela Merkel provided the impetus for action and blazed forth on her own path to enhancing EU resilience. While her bold initiative was crucial to ending the EU’s stasis, she has been harshly criticized by some countries, particularly Eastern European ones, for “moral imperialism.” Furthermore, with support for her party declining and the extreme right movements on the rise, Merkel may be confronted with the need to again raise support within her own country with the prospect of the 2017 general elections.

The European Union, whose member states are unable to ease their individual security-focused understanding of foreign policy, is in certain division. The Dublin system fell under the weight of large-scale arrivals and did not ensure a fair share of responsibility for asylum applications across the Union. The discussion over the resettlement and relocation quota system sparked a rift between some Western European countries that backed this idea and several Eastern European countries, namely Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia, which harshly opposed taking any migrants or asylum seekers. Amid fierce opposition from Eastern European countries, on May 4, 2016, the European Commission pushed forward with a proposal to reform the Dublin Regulation. The proposal included a “fairness mechanism” under which asylum request quotas would be established to reflect the national population and wealth of a country. According to this new proposal, states could also refuse to take asylum seekers by paying 250,000 EUR per each person rejected. Although this seems to be the only feasible way out of the impasse, Eastern European countries are still opposing the plan: Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán will tour European capitals to push for a new 10-point plan for the protection of the EU’s external borders and free movement within the community. In the meantime, the EU-Turkey deal itself calls into question the EU commitment to human rights and its own core values.

The situation requires further attention in the following areas:

- Amid opposition from certain European countries, the relocation and resettlement plan stands as the one feasible proposal to address the solidarity crisis and reform the Dublin system. However, it lacks practical information about how member states are supposed to enforce it and to ensure that asylum seekers will present their requests in the countries to which they are sent. European institutions should take into account asylum seekers’ preferences and, in particular, family ties and language. This will avoid the need for secondary movements and multiple applications across the EU.

- As the EU-Turkey deal comes into force, the likely result will be the emergence of new migratory routes and the reactivation of older ones, such as the Central Mediterranean route. UNHCR data shows that arrivals in Italy began surging in the month of March, while at the same time decreasing in Greece. The Central Mediterranean route, which connects North Africa to Italy and Malta, is known to be the deadliest among the Mediterranean’s routes. European institutions should take this issue into account, addressing the phenomenon of route shifting before another emergency occurs.

- With local and international organizations winding down or suspending their operations on the Greek islands and with Greece in increasing need of technical support, it will be difficult to ensure the implementation of the EU-Turkey plan. For this reason the EU should compromise with civil society organizations and provide them funding. Such organizations are needed to monitor the implementation of the plan and ensure that it meets international human rights standards.

- The 72,000 Syrians that the EU has promised to take in is an inadequate number, considering the one million migrants and refugees who reached Europe in 2015 and the 2.7 million Syrians already in Turkey. Member states need to collectively increase their pledges, thus countering the crisis of inter-state solidarity.

- A communication strategy to reach out to the Turkish public should be developed. In some districts, discontent is turning into open protest as the number of refugees increases. In the province of Dikili (İzmir), for example, residents are protesting the plan to build a refugee camp on the outskirts of the town. The discussion over the EU-Turkey plan has been solely at the state level so far, and there has not been any in-depth analysis of public opinion. The deal carries the risk that Turkish public opinion will deteriorate regarding the EU.

- There must be a greater degree of transparency regarding the usage of EU funds given to Turkey. The money should be used solely for improving the living conditions of refugees inside Turkey and audited by transparent national and international mechanisms, together with civil society organizations.

- The solution to the migration crisis should come from European institutions, and responsibility should be shared among member states in order to prevent a single country from shouldering the weight of proposing solutions. A single member state, i.e. Angela Merkel’s Germany, does not have the legitimacy or the authority to put forward policy that will affect the EU and all its member states as a whole. If the EU fails to develop a united solution to the refugee crisis, the European project will suffer a severe blow, exposing a bleak future for EU integration. Rather than crumbling under the pressure to formulate an immediate, singular solution, this challenge should be seen as an opportunity to build a more united Europe in the long term.

At the time of publication, rumors had spread that the Europe Union is seeking a plan B to solve the migration crisis. Despite human rights and legal issues surrounding the EU-Turkey deal, in the end it will be Turkey’s domestic political instability that will undermine the deal. The growing power struggle inside the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) has reached its own peak and Turkish Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu was forced to resign in May 2016. With the change of the Turkish prime ministry as well as the Minister for EU Affairs, the EU has lost their Turkish counterparts in the deal with Turkey. Additionally, visa-free travel is in a deadlock after Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan underlined that there will be no change in the definition of terrorism, which is one of the five remaining benchmarks before implementation. The deal has been the EU’s boldest attempt to tackle the migration crisis. However, by putting its eggs in one basket, the EU took a grave risk betting on Turkey and might now be back to square one.

Leave a Reply