* This policy brief has been published by Istanbul Policy Center (with Melih Özsöz).

Executive Summary

Relations between Turkey and the European Union (EU) have been unexpectedly revitalized since October 2015 by the current refugee crisis, which compelled the EU to seek Turkey’s partnership in order to solve its migration problem. However, the timing of the agreement and subsequent revitalization of membership talks after years of stalemate is quite problematic given the situation regarding the internal affairs of the country as well as the international conjuncture. The current “recovery” of Turkey-EU relations has not only been used as an electoral opportunity right before the country’s critical elections in November 2015 but has also served as validation of— or at least the EU’s willingness to turn a blind eye to—the deterioration of rule of law, democracy, basic rights and freedoms. Realpolitik has taken over the value-based anchor of EU membership and left Turkish citizens with vague promises. In addition, since the optimum solution for refugees deserves a more complex and farsighted policy, not just a political brokering, there has been very little progress regarding the situation. All these developments have led to the questioning of the relationship or partnership that Turkey has with the EU. In light of the current situation, it must be posited if the Turkey-EU relationship has developed into a kind of geostrategic partnership rather than a value-based alliance. In this paper, Turkey’s accession negotiations are revisited on the 10th anniversary of their beginning with a special focus on the current situation of negotiation chapters, the Cyprus issue, and the potential revision of the Customs Union. The paper will then discuss the refugee deal, including the possibility of visa-free travel for Turkish nationals. Turning the focus to the EU specifically, the new generation of progress reports will be analyzed as a tool for enlargement in addition to a general review of the current situation in the EU: First the economic crisis and then the refugee crisis have put the European project itself in a very difficult position, shaking the Euro and the Schengen Agreement from their roots. All in all, Turkey and the EU, as well as bilateral relations, will be analyzed taking into consideration the current internal and external challenges.

.

Introduction

Turkey, after the establishment of the Republic, has always been an ally of Europe. It became a member of the Council of Europe (CoE) in 1949, a member of NATO in 1952, and applied for membership to the European Economic Community in 1959, only one year after its establishment. The official partnership between Turkey and the EU began after signing the Ankara Agreement in 1963. Turkey was awarded EU candidacy status in 1999, with negotiations starting in 2005. Today, the refugee deal seems to dominate talks between Turkey and the EU; however, there is a wider set of underlying issues that play an important role regarding the discussion of the Turkey-EU relations. This paper, which approaches Turkey-EU relations from a broad perspective, aims to elaborate on those issues as a testimony to the 10th anniversary of accession negotiations. First, the current state of the Turkey-EU relations will be analyzed. Second, the Cyprus issue, which may play a key role in unblocking negotiation chapters, will be examined. The paper will continue with a discussion of the Customs Union, which has been a keystone of the integration process between Turkey and the EU, and its potential revision by the end of 2016. The focus will then turn to another prevalent topic: visa liberalization for Turkish citizens. Visa freedom has been on the table for almost a decade now; however, it is not until recently that liberalization has been able to act as the most important “carrot” for Turkey in the negotiation of the refugee deal. After the discussion of Turkey-EU relations, the page is turned to Europe itself and its current challenges. A series of questions are raised in regards to this: How should we read the new generation of progress reports? Are these reports part of a larger, more innovative step towards a new kind of enlargement (or better said neighborhood) policy from the European Commission? Do such reports reflect a change in the EU’s mentality—no to enlargement, yes to neighborhood? What are the impacts of the economic and refugee crises on European integration? All in all, a more realistic approach is needed to assess Turkey’s future in Europe, keeping in mind historical relations and pending promises.

.

Turkey-EU Accession Negotiations: Current State of Play

Before obtaining EU membership, candidate countries are required to fulfill all criteria within the EU acquis. 1 In the case of Turkey, so far 15 chapters have been opened, and one chapter has been provisionally closed. While 16 chapters are still being blocked by two member states, namely Cyprus and France, the European Council’s decision not to close any chapters until Turkey allows Cypriot ships and airplanes to use its ports and airports stands as a major problem to Turkey’s accession negotiations. However, on the other side of the coin, Turkey’s stance remains unchanged in spite of this; by not extending the 1995 Customs Union Agreement to all member states, Turkey is allowing its bilateral issues to overshadow its membership process.

In recent years, experts both in Turkey and in Europe have articulated the absurdity of opening a chapter without the ability to close it. However, the current state of play in the opening of acquis chapters in fact offers a solid way to evaluate Turkey’s progress on its EU path. The number of chapters opened each year has dramatically decreased after 2008. The first chapter was opened in 2006, followed by the opening of five chapters in 2007 and four chapters in 2008. Over the course of the next two years, in 2009 and 2010, a total of three chapters were opened. Following this, in 2011, 2012, and the first half of 2013, Turkey’s negotiation talks gradually came to a complete halt as five Presidencies of the Council could not manage to open any chapters on accession talks with Turkey. This “static” period finally ended in November 2013 when the Latvian Presidency opened chapter 22 on Regional Policy and Coordination of Structural Instruments. While the opening of one chapter after two and a half years of silence raised hopes for Turkey’s EU track, no chapters were opened in 2014 or 2015, with the exception of chapter 17 on Economic and Monetary Policy being opened just two weeks before the end of 2015 and Luxembourg’s Presidency Council of the EU. However, one should also note that the opening of this latest chapter coincided with the refugee deal reached between Turkey and the EU at the end of November.

All in all, in the 10th year of accession talks, Turkey has only been able to open a total of 15 chapters, not even half of the list. When this timeline is compared to Croatia, for instance, which became a candidate country in 2005 like Turkey, the picture becomes even more striking. As the two countries began accession talks on the same day in Brussels, the one has enjoyed EU membership since 2013, while the other is still on the waiting list with only half of its chapters opened and one provisionally closed.

Certainly, the last five years of the negotiation talks have taken an unusual path. With Turkey’s deteriorating performance on fundamental rights and freedoms and the EU expressing its concerns, leaders on both sides have repeatedly voiced the need to open chapter 23 on Judiciary and Fundamental Rights immediately. While the same applies for chapter 24 on Justice, Freedom, and Security, no concrete action has been taken by the EU towards lifting blockages on these chapters— although the Commission proposed to establish “working groups” for concerned chapters within the framework of the Positive Agenda in order to help Turkey meet necessary opening benchmarks. Despite years of reciprocal messaging on both sides, none of these urgent chapters for Turkey could be opened. The same applies to the chapters on energy, trade, and foreign policy as well. This clearly shows the hesitation within the EU’s 28-member block and the impossibility of persuading some members of the EU towards removing blockages. In short, the main windows of collaboration and interaction still remain closed. In addition, the EU is insufficiently using its soft power over Turkey regarding the fundamental rights and freedoms.

.

Cyprus Issue: Closer Than Ever to a Settlement?

The Cyprus issue, which has been the subject of countless initiatives, has been in the spotlight of the international community for decades. The focus of the issue shifted following the unilateral membership of the Greek Cypriot Administration as the sole “legitimate” representative of the island to the EU in May 2004. The EU’s asymmetrical use of conditionality—linked to its failure to exercise much needed pressure on the Greek Cypriot side to say “yes” to the Annan Plan on April 2004, just days before Cyprus’s assent to EU membership— resulted in the EU’s admittance of a divided island into its “unified” cohort of member states. This has in turn made the EU a larger party to the debate while still maintaining the division of the island. As the EU authorities expressed their regrets about the result of the referendum, the Republic of Cyprus was given the power to veto the opening of all EU chapters related to Turkey. Moreover, the commitments made by the EU to the Turkish Cypriot Community, including 259 million euros to be given to Northern Cyprus over three years and the opening of direct trade between the EU and Northern Cyprus, could not materialize due to the Greek Cypriot veto in the Council of Ministers.

Further, failure to resolve the problems and the attitudes of Greek Cypriots with regards to the rest of the island created a negative atmosphere within Cyprus, especially in the northern half. In the minds of Turkish Cypriots, the northern part of the island was in essence punished for its collaborative attitude and strong “yes” vote for the Annan Plan. The Annan Plan was regarded as the most solid chance for a peaceful settlement, and after a series of failed negotiation attempts following its rejection, there was little hope left for unifying the island. While goodwill has always surrounded the idea of a settlement, very little political will had been shown. A new hopeful beginning was initiated in February 2014 with the Joint Statement2 agreed to by Greek Cypriot leader Nicos Anastasiades and then Turkish Cypriot President Derviş Eroğlu; however, this process was also wiped out, with the Greek Cypriot side leaving the negotiation table due to a disagreement over the hydrocarbon resources around the island.

Thus, today the solution for a unified and peaceful Cyprus needs to be approached carefully. The victory of Mustafa Akıncı over President Eroğlu in the Turkish Cypriot presidential elections has injected new desire into the negotiation process, coupled with much needed political will, and led to the reopening of talks in May 2015. So far the progress on negotiations is promising, and there are several reasons to believe this new process could be accelerated. First, this is the only time both Greek and Cypriot leaders—Anastasiades and Eroğlu each having previously campaigned in favor of the Annan Plan—have sat around the table genuinely interested in reaching a settlement. Second, the negotiation process is coming from inside. Third, the financial crisis in Southern Europe, from which the Republic of Cyprus has had its share of problems, has increased political will. Lastly, since three guarantors (the United Kingdom, Greece, and potentially Turkey) are merging in support of a potential solution, a peaceful settlement on the Cyprus issue is more likely.

In short, there is a real chance that a settlement to the decades-long Cyprus issue could soon be witnessed and put to simultaneous referenda in both the North and the South. Both communities, as well as the international community, have a lot to gain from reunification. However, one should remember that despite numerous attempts the reunification of Cyprus is still a delicate issue. With the recent developments in the Middle East in general, Syria in particular, the strategic importance of the island for Turkey has been magnified. For this reason, Turkey’s attitude towards the settlement and its insistence on its military existence on the island are particularly important. Even if the political will on the island is greater than ever, the achievement of any positive result is dependent on a variety of factors.

.

Turkey-EU Customs Union: Breaking the Routine

The Turkey-EU Customs Union is a cornerstone of Turkey’s European integration. In May 2015, Turkey and the EU announced for the first time their decision to revise the framework and to expand the scope of the Customs Union, which was established 20 years ago in 1996. Back then the Customs Union, promoted as the road to EU membership, served as a definite tool for Turkish industry, trade, and business to open up to Europe and the rest of the world. It has since been heavily criticized mainly by the Turkish business community due to the unbalanced situation it has created, especially following the EU-U.S. initiative to create a global trade area through the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) process.

Criticism with regard to the functioning of the Customs Union has focused on three main areas. First and foremost, Turkey has been largely absent in the EU negotiation processes of trade agreements with third countries, most significantly TTIP, even though such treaties have the capacity to severely affect the Turkish economy. For example, according to the World Bank’s evaluation of the Turkey-EU Customs Union, it is estimated that Turkey will face a welfare loss of at least 130 million USD due to TTIP.3 Secondly, quotas applied to Turkish trucks on exports and imports disregard the notion of competition, which was implied in the signing of the Union 20 years ago but not accounted for in this regard. Lastly, the visa restrictions placed on Turkish businessmen not accounted for in the Customs Union jeopardize the free competition principle of any trade agreement.

With these developments, the 20-year-old framework of the Customs Union has become outdated. The Turkey-EU Customs Union must now be urgently revised not only in light of the new global tendencies of world trade but also in light of shortcomings resulting from Turkey’s absence in the decision-making process and the barriers encountered in the free movement of goods and persons. In this respect, it is essential not only to revise the framework of the Customs Union but also to expand the scope of the agreement to new areas such as agriculture, service, and public procurement.

However, several problems remain on the surface. Among them, Turkey’s ability to negotiate on such a huge and full-fledged agreement stands as the biggest challenge. Both parties have limited time to make the necessary impact assessments and consult with stakeholders before sitting at the negotiating table. Both sides will progressively work toward ensuring Turkey’s economic standing, but Turkey’s capacity to negotiate in such an agreement carries a question mark, especially compared to the EU, who has negotiated many substantial agreements (like TTIP and the Trans-Pacific Partnership – TPP) in the last few years with many third countries.

In order to better determine Turkey’s position during the negotiation on the revision of the Customs Union, it is of the utmost importance that private sector participation in the consultation process is enhanced. But while stakeholders will share their specific demands with public authorities, in order to create a win-win situation in the revision of the Customs Union, the Turkish side needs to be ready to make concessions with the European side, mainly in the agricultural sector.

.

While There Is Still a Schengen Agreement: Turkey-EU Visa Liberalization Talks and the Refugee Crisis

The visa policy of EU member states towards Turkish nationals has been a long-debated issue in Turkey-EU relations. The problems gloss over a wide spectrum, ranging from the fact that visa requirements are contrary to the Turkey-EU Association Law to the cumbersome mechanisms associated with the visa procedure such as the hefty fees requested, number and nature of documents that need to be submitted, and frequent disrespectful treatment of Turkish citizens by consular staff.

Today, Turkey is the only EU candidate country whose nationals are obliged to obtain a Schengen visa before entering the EU. According to a study by the Economic Development Foundation (IKV), over the six years included in the study (from 2008 to 2014) Turkish nationals have paid 250 million euros, not counting shadow costs, for the C type Schengen visa application valid only for short-term visits.4 While restriction of movement for Turkish citizens has been a problem since the 1980s, with Germany being the first European state requiring visas from Turkish nationals as a “temporary procedure,” the EU has been reluctant to propose a visa liberalization process for Turkey like the one it has established with the Western Balkan countries and which it is still negotiating with Ukraine, Moldova, and Russia. With such longstanding regulations still in place, the “temporary” visa has become a permanent procedure.

Since 2013, most of the attention has been canalized on the EU-Turkey Readmission Agreement as the legal discussion over visa-free travel for Turkish nationals was blurred by two cases in the European Court of Justice (ECJ). In 2008, the ECJ’s Soysal decision, in which the Court ruled that visas applied to Turkish service providers are in breach of the Additional Protocol, revitalized the legal discussion over the visa issue. However, in 2013 the ECJ gave a contrasting decision in the Demirkan case, in which it ruled that the visa requirement for Turkish service providers is in line with the EU acquis. Therefore, a possible legal solution to the visa problem was lost, and Turkey has been left with the Readmission Agreement, which it has been negotiating with the EU since 2003.

Readmission negotiations had been at a stalemate for a long time because of major disagreements between the two sides. Eventually, Turkey, having come home empty-handed after its struggles in the European courtrooms, was pressured into signing the readmission agreement in December 2013. Following the signing, a visa liberalization dialogue and roadmap under five thematic blocks were given to Turkey to fulfill.5 The impetus gained by the signing of the readmission agreement and the launch of the visa-free dialogue for Turkish nationals has been reinvigorated with the current refugee crisis in Europe. European leaders, suddenly faced with an influx of people, pushed the panic button and asked for Turkey’s involvement to overcome this problem, hoping the candidate country could help alleviate the sudden flow of migrants to European borders. Just before the elections in Turkey on November 1, 2015, top Commission officials and German Chancellor Angela Merkel— who has been a defender of alternatives to Turkey’s EU membership such as a privileged partnership— visited Turkey to finalize the deal. Certain promises have been given to Turkey, ranging from 3 billion euros of financial support to the opening of new chapters in the accession negotiations. A common declaration was signed a few weeks after the elections. For the first time in the history of the visa struggle, an exact date for visa free travel was pronounced in Brussels: October 2016. But, this is only conditional upon Turkey fulfilling criteria listed on the roadmap and effectively applying the readmission agreement.

On the Turkish side, it is hard to say that the borders are fully secured and controlled. In addition, Turkey continues its open door policy in the East without a proper refugee registration system. Another issue is the calendar: Turkey needs to barrel through its to-do list within a relatively short period of time in order to meet with the EU roadmap. The requirements of the roadmap range from Turkey’s restriction of visas to third country nationals, including Syria, to its withdrawal of objections to the Geneva Convention Article 5 on recognition of refugees. In addition, the change of all Turkish passports and the establishment of an effective integrated border management system are also listed. Turkey has just a few months—until October 2016—to implement these changes, which puts the promise of visa-free travel for Turkish nationals in danger. Still, despite Turkey’s grim possibility of actually achieving these changes, the Turkish government uses visa liberalization as an internal campaign tool and claims that this target will be achieved. The real roadmap until October 2016, however, remains questionable.

On the European side, the promises given in the EU-Turkey leaders summit on November 29, 2015 have been blurred by the present reality, and the current state of the refugee crisis is not as amicable as one may have hoped. While member states have been disputing provisions regarding the financing of the EU-Turkey agreement, the amount of refugees illegally passing into the EU, many who are tragically losing their lives in the risky crossing of the Aegean, has only continued to increase. Italy first objected to this plan for budgetary reasons; however, many other member states have since followed suit. Eventually, German Chancellor Merkel saved the plan by convincing Italy to comply despite its budgetary concerns. The Commission collectively approved the plan and declared the 3 billion euro fund open to Turkey. However, it remains to be asked how the transparency, efficiency, and effectiveness of this amount of money will be guaranteed, as well as the collective future of a concerted Europe.

.

Enlarging Europe: How to Read the NextGeneration Progress Reports

While Turkey-EU relations follow its own path, European integration has its separate challenges. Enlargement, in particular, with its own set of dynamics is going through an ambiguous and puzzling phase. One and a half years after Commission President Jean-Claude Junker’s statement announcing that Europe will not be enlarging its borders until 2019, the European Commission appeared to move one step toward future enlargement with an innovative change in its annual process of evaluation for candidate countries, including Turkey, ushering in a new generation of progress reports.

The European Commission published its first progress report on Turkey in 1998. This 57-page report established a monitoring process and opened the doors of the candidacy process for Turkey following the approval of the second report at the Helsinki Summit in 1999. The 2015 Turkey Progress Report, which is the 18th and the most recent report on Turkey, was published by the European Commission on November 10, 2015, having been delayed one month after the “secret” request of the Turkish government to do so in return for an EU-brokered refugee deal.

The European Commission so far has evaluated progress in Turkey through its corpus of 18 reports, with the total number of pages reaching 1,878. The amount of pages the European Commission has so far prepared for Turkey Progress Reports is seven times greater than the amount of pages included in the Treaty of Lisbon. Unfortunately, the 1,878 pages of the progress reports have so far been an insufficient tool in steering Turkey toward EU membership. Throughout the years, the reports have become monotonous, limited in scope, and less effective. While the European Commission has become a constant critic and offered few and far-ranging solutions, Turkey has done something that no candidate country has ever done before: As a response to the Commission, Turkey started to publish its own progress reports in 2011. Without doubt, the European Commission’s Progress Reports on Turkey, as well as “chapter openings,” serve as an important tool to create the illusion of an ongoing membership process. However, in conjunction with the decline in the credibility of Turkey’s EU accession negotiations in both Turkey and Europe, as well as Turkey’s membership goal, it is impossible for the progress reports to act as effective tools to trigger Turkey’s reform process.

Thus, with the intention to overcome these limitations, mainly with Turkey, the European Commission decided to change the way the progress reports are written. While the first “nextgeneration progress reports” were published in November 2015, the reports were welcomed by all candidate countries as they contain a clearer, standardized terminology and language; recommendations tailored to each candidate; and an approach that assesses both the developments of the last year and the accession process as a whole.

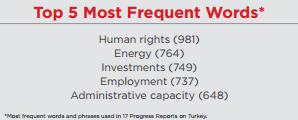

It will be interesting to see what the next-generation progress reports will highlight in comparison to the first 17 reports—if they will prove any different at all. Analyzed in a study by IKV, the terminology of the reports reveals the predominant themes within Turkey’s first 17 progress reports.6 The five most frequently used terms in the reports are “human rights,” “energy,” “investments,” “unemployment,” and “administrative capacity.” The European Commission has repeated “human rights” 981 times throughout its 17 progress reports, thus spotlighting the issue. With regards to rights and freedoms, human rights often appears together with the words “torture” and “freedom of expression,” two other terms that are most frequently used by the Commission in this context.

Although Turkey’s latest progress report includes several warnings, especially with regard to problems in the implementation of political criteria, it also contains encouragement for Turkey to keep pursuing its path toward EU membership.

However, for the first time the report also notes major backsliding being observed in three areas: freedom of expression, freedom of association and assembly, and public procurement.

.

From Economic Crisis to Refugee Crisis: Europe Today

The EU has faced various problems over the past decades. The most important of these are related to the economy. Since the establishment of a single market under the Single European Act (SEA) on December 31, 1992 and the later agreement on the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) in 1999–which includes the creation of the common currency “Euro” and European Central Bank (ECB)—the policy impact of the EU has been magnified. Following this, economic crises have affected the continent as a whole, having not only economic but also political consequences for European integration. The name “Troika”–the governing body over the public debt crisis in the Eurozone countries consisting of the European Commission (EC), the European Central Bank (ECB), and the International Monetary Fund (IMF)– began to be heard in daily news all around Europe.

This situation has triggered a severe reaction throughout both debtor and creditor countries in the EU. Northerners, aka creditors, are more nationalist than ever, while Southerners, aka debtors, are mainly anti-austerity after years of experience with different economic programs. Some members of the former group have come out as strong opponents of European integration–it could be said that maybe some had never been fans to begin with–while the latter group has expressed its desire for a “better” European Union, said in a very general manner. This environment has led to a rise in Euroskeptic voters in many countries. Summit after summit, EU leaders have failed to produce a solid solution to the crisis, proving the deficiencies of European leadership.

As Europe began to slowly recover from the economic crisis, however, a second challenge has quite literally entered Europe’s borders: the refugee crisis. Today, there are over 1 million asylum seekers within Europe, and more are expected to come. This situation has reached the point of endangering the Schengen Agreement itself, as member states are divided on how to manage the current situation and some countries have even sought to re-establish their internal borders.7 It is clear that the future of European integration will rely on a clear and effective solution of this crisis. Two camps are visible among the member states. The first camp is led by Germany, who is trying to reach a communitarian deal that may mobilize the EU as a whole. Other members, mainly Hungary, who are looking for an intergovernmental solution, lead the second. In the midst of the controversy the pressure on Greece is constantly increasing. Rumor has it that the Schengen border will be moved to the north, threatening to leave the country outside the Schengen area for two years if the situation continues.8

In the meantime, the European Commission has also decided to take action by announcing the establishment of the “European Border and Coastal Guard,” which was proposed on December 15, 2015.9 This envisaged new agency will change the idea behind Frontex, the present EU agency designed to guard the EU’s external border, as well as the EU’s other related border operations. The new agency will monitor external borders, hiring a pool of new European border guards, and have the right to intervene in EU border controls when necessary. The agency will also initiate a new mandate to send liaison officers to and launch joint operations with neighboring third countries, including operations on their territory.10 This is a symbolic step towards building a European army, establishing Europe as fortress rather than a value-based community.

.

Conclusion

Turkey-EU relations have gone through different phases throughout decades while agreements, promises, and the focus of the relationship are greatly shifting nowadays. Turkey-EU relations were first built from the Customs Union, the cornerstone of economic integration. The relationship then progressed via Turkey’s candidacy and accession talks, which provided the EU an important opportunity to improve various dimensions within Turkey through the application of the acquis. The Cyprus issue and visa-free travel, with all its implications from legal to social and political to economic, have been on the table for a long time. While there is hope for a peaceful solution to the Cyprus problem, and the visa issue has recently taken a new form under the refugee deal, both require concrete steps before either is completely solved.

In short, on the bitter 10th anniversary of the opening of Turkey’s EU accession negotiations, several aspects of Turkey’s present predicament pose barriers to its full membership:

• a move away from the Copenhagen criteria regarding basic rights and freedoms;

• 15 negotiation chapters open out of 33, with 16 being blocked and none likely to be closed due to certain blockage;

• a 20-year-old Customs Union requiring a lengthy revision process;

• a cautious hope for the re-unification of Cyprus after almost half a century of division and the possible removal of chapter blockages;

• an unclear roadmap to the resolution of a 30-year-old visa problem that cost Turkish citizens tremendous amounts of money, effort, and time; and most recently,

• a refugee crisis that effects both the future of European integration and Turkey-EU relations.

After 10 years of accession negotiations, Turkey and the EU are still trying to find solutions to old problems. This is coupled with vague promises and unclear roadmaps that serve only one purpose: the deterioration of mutual trust and loosening of the European anchor for Turkey’s development. In short, these obstacles have derailed Turkey from its European path.

For this reason, the present Turkey-EU relationship looks to be moving towards a strategic partnership or an ad hoc cooperation rather than a value-based path towards full membership. Actors are moved by realpolitik, shaking hands on temporary solutions to deep-seeded, age-old problems. Unfortunately this mindset is destined to fail, and the current state of play is nothing more than an illusion of candidacy with no concrete future in sight.

The refugee crisis is the most urgent problem waiting for a solution. Turkey should cooperate bilaterally with member states that are willing to do so. Germany is already looking for an alternative plan with Turkey under the umbrella of the European Stability Initiative (ESI).11 A common decision can take a long time since some leaders are firmly against relocation quotas such as Victor Orban of Hungary, who called for a referendum rejecting the European Commission’s plan. Even though the EU’s promised 3 billion euros has been approved, there is no clear plan yet on how to use it. It is very important that the process is transparent and related bodies are included in the decision making, leaving no room for speculation.

Turkey has its own responsibilities in addition to the EU such as fighting human trafficking, which is already considered a crime according to Turkish law. The country’s decision to extend work permits to immigrants in order to incentivize them to stay has been welcomed by its European counterparts; however, the creation of a significant amount of new jobs is thus also required, as well as implementing new policies to integrate refugees into society. All in all, there is no easy fix to this issue, which will be dealt with in the long-term.

.

END NOTES

1 | “Conditions for membership,” European Commission, accessed February 29, 2016, http:// ec.europa.eu/enlargement/policy/conditionsmembership/index_en.htm.

2 | “Resumption of the Negotiation Process in 2014,” Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus – Ministry of Foreign Affairs, accessed February 29, 2016, http://mfa.gov.ct.tr/cyprus-negotiationprocess/cyprus-negotiations/resumption-of-thenegotiation-process/.

3 | “Evaluation of the EU-Turkey Customs Union,” World Bank, March 28, 2014, accessed February 29, 2016, http://www.worldbank.org/content/dam/ Worldbank/document/eca/turkey/tr-eu-customsunion-eng.pdf.

4 | Melih Özsöz, Ahmet Ceran, “Yasadışı Göç ve Vize Serbestliği ekseninde AB ve Türkiye: Ortak Sorun-Orta Çüzüm,” İKV Değerlendirme Notu, ed. İktisadi Kalkınma Vakfı (Istanbul: İktisadi Kalkınma Vakfı, 2015), 1-10, accessed February 29, 2016, http://www.ikv.org.tr/images/files/IKV%20 degerlendirme%20notu_140_pdf.pdf.

5 | “Roadmap – Towards a Visa-Free Regime with Turkey,” European Commission, December 16, 2013, accessed February 29, 2016, http:// ec.europa.eu/dgs/home-affairs/what-is-new/ news/news/docs/20131216-roadmap_towards_ the_visa-free_regime_with_turkey_en.pdf.

6 | Melih Özsöz, Büşra Çatır, Ahmet Ceran, “İlerleme Raporlarına Derinlemesine Bir Bakış: Avrupa Komisyonu İlerleme Raporlarının Matematiği Ve Dili,” İktisadi Kalkınma Vakfı, accessed February 29, 2016, http://www.ikv.org.tr/ ikv.asp?id=1194.

7 | Jacopo Barigazzi, “EU pushes ‘worst-case scenario’ to stem migrant crisis,” Politico.eu, January 25, 2016, accessed February 29, 2016, http://www.politico.eu/article/eu-possibleextension-schengen-border-control/.

8 | Matthew Holehouse, “Greece faces being sealed off from Europe to stop migrant flow in move that creates ‘cemetry of souls’,” The Telegraph, January 25, 2016, accessed February 29, 2016, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/ worldnews/europe/eu/12119799/Greecethreatened-with-expulsion-from-Schengen-freemovement-zone.html.

9 | “A European Border and Coast Guard to protect Europe’s External Borders,” European Commission, December 15, 2015, accessed February 29, 2016, http://europa.eu/rapid/pressrelease_IP-15-6327_en.htm.

10 | “Securing Europe’s External Borders – A European Border and Coast Guard,” European Commission, last modified January 13, 2016, accessed February 29, 2016, http://ec.europa.eu/ dgs/home-affairs/what-we-do/policies/securingeu-borders/fact-sheets/docs/a_european_ border_and_coast_guard_en.pdf.

11 | “Refugee Crisis: A breakthrough is possible,” European Stability Initiative, February 19, 2016, accessed February 29, 2016, http://www.esiweb. org/index.php?lang=en&id=67&newsletter_ID=103.

Leave a Reply