* This article has been published by London School of Economics European Policy and Politics (EUROPP) Blog

The November elections were a huge gamble for Turkey: a gamble wagered and won. President Erdoğan and his Justice and Development Party (AKP) put all their cards on the table and in turn got what they wanted: single party rule. After failing to form a coalition in June, or rather lacking the will to be in one, the President called snap elections for the first time in the country’s history, and Turkey went to the ballot box for the second time in five months. The participation rate was again very high – especially compared to other European countries – as 85.6 per cent of the electorate cast their vote. However, the results were very different from that of the June election, altering the parliamentary dynamics, again.

To understand the reasons behind this change, it is necessary to look deeper into our general understanding of Turkish society. Turkey is dominated by right-wing voters, mostly conservatives and nationalists. These right-wing voters are divided between the conservative AKP and nationalist Nationalist Movement Party (MHP). On the other end of the spectrum, the 2015 general elections saw the rise of a leftist, Kurdish division in mainstream politics. While the People’s Democratic Party (HDP) drew a significant amount of votes from Kurds and the political left, the Kurdish people as a whole were generally divided between the HDP and AKP.

In the five months between the two elections, Turkey had gone through drastic changes. The ceasefire between the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) and the government was called off. Violence had escalated across Turkey, and martial law had been imposed on some regions in the south-east. The PKK responded to the government’s attacks with more counter attacks, which also damaged the image of the HDP. HDP buildings were constantly under attack, and HDP supporters were threatened with judiciary processes.

The opposition had been silenced by police intervention in mass protests, attacks on media buildings, and the government’s media confiscations. Two significant massacres were carried out by alleged suicide bombers in Suruç and in Ankara, killing over 130 people in total and injuring dozens more. The government was accused of not ensuring security in the area although they had the necessary intelligence about the suspects. Amidst the violence, the economy had continued to fall further into the red. In the end, people were scared and voted for stability, the principle on which the AKP had campaigned reflected this.

What has changed in Turkey?

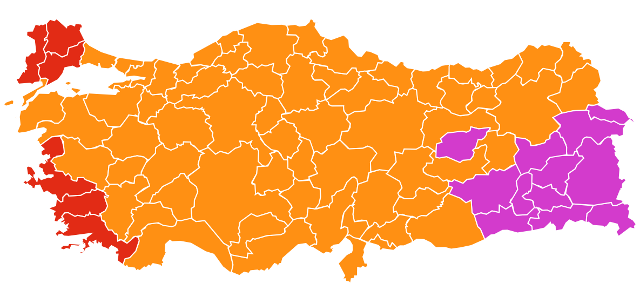

There are 81 cities divided into 85 electoral districts across Turkey. The AKP kept or raised its vote share in all the districts it won in June, and the electoral map of Turkey was once again dominated by AKP votes. According to preliminary results, the AKP received 49.48 per cent of the votes and 317 parliamentary seats. This is a significant increase from the June results – an increase nobody, including party members, had expected. Figure 1 below shows the new electoral map of Turkey.

Figure 1: Electoral map of Turkey

Note: Orange represents areas where the AKP was the most popular party; red indicates areas where the CHP was the most popular party; and blue indicates areas where the HDP had the most support. Source: CNN Turk

There are three main sources for the increase in AKP support: first, the nationalist vote that shifted from the MHP to the AKP; second, the conservative Kurdish vote that came from the HDP; and third, support stemming from the voters of BBP-Saadet (a nationalist Islamist coalition that ran for election in June). Aside from these vote shifts, the AKP also attracted a number of resentful voters who did not go to the ballot box in the previous election.

Turkey’s main opposition party, the Republican People’s Party (CHP, which was responsible for establishing the Turkish Republic in 1923), gained 25.31 per cent of the vote and 134 seats in parliament. Even though party leader Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu had been the most positively viewed figure in the pre-electoral term, the party could not duly express its position on the issues dominating this specific election. The CHP’s pledges have historically been very attractive; however, the party failed to respond to the current needs of the country.

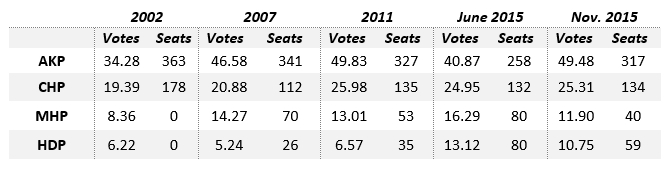

Table: Percentage vote shares and seats in recent Turkish elections

Source: The Supreme Electoral Council of Turkey (2002-2015I), CNN Turk for November 2015

The MHP obtained 11.9 per cent of the vote, winning the least amount of seats of any party in parliament. The party can be seen as the biggest loser of this election, and many blame the party’s leader, Devlet Bahceli, for the result. The MHP’s supporters attribute the loss to Bahceli’s negative attitude in coalition negotiations and his unwillingness to cooperate and agree to every opportunity presented to him for forming a coalition. Ultimately, the MHP missed its chance to be a major player in the country’s political game.

Although the HDP lost a significant amount of domestic voters compared to the June elections, the party still managed to pass the 10 per cent electoral threshold thanks in no small part to the overseas vote, obtaining the right to enter parliament with 59 seats – albeit this is 21 seats less than it obtained in June – and more than one million popular votes.

It should again be emphasised that the HDP had a very difficult pre-electoral period. The HDP stopped all campaigning after the Ankara massacre. A significant amount of Kurds had deflected to the AKP, afraid that the election of the HDP and failure of the AKP would mark a return to the terror of the 1990s and instability in the south-east. In addition, a number of Turks from the western part of Turkey had second thoughts about supporting the party, having accused the HDP of not distancing itself from the PKK.

The future of Turkish politics

Fears over how free and fair the elections would be played an important role in the campaign. Concern over potential electoral fraud, as was the case in the June elections, motivated civil society to form the largest voluntary organisation in Turkish history working on electoral fraud, ‘Vote and Beyond’, which managed to mobilise more than 65,000 volunteers.

The final report of the organisation concluded that there was no systematic fraud in the voting process. This fits with the report of independent observers of OSCEPA (Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe Parliamentary Assembly); however, the organisation further claimed that “elections in Turkey offered voters a variety of choices, but the process was hindered by the challenging security environment, incidents of violence and restrictions against media”.

Turkey will continue to be ruled by a single party for four more years. A number of challenges will need to be met by the new government including a failing economy, a revision of foreign policy that adapts to contemporary developments, and a democratic and sustainable solution to terrorist activity. Turkish society is strongly divided as many are concerned about the AKP’s continued push away from parliamentarism and toward presidentialism.

There is also heightened anxiety regarding pressure against the opposition in general – media representatives and journalists in particular – the suppression of Kurdish demands for democratisation, the potential manipulation of Kurds to achieve the shift to a presidential system in parliament, and the use of the Syrian crisis for internal political gain. However, let’s hope that the AKP and Erdoğan’s lack of electoral pressure over the next four years will revive the peace process with the Kurds and facilitate steps towards further democratisation and compliance with EU standards of human rights, justice, and freedom of the press and expression.

Leave a Reply